Digital Entrepreneurship 1955–2026: From the first Silicon Valley to GenAI—and back

- Andrea Viliotti

- 3 giorni fa

- Tempo di lettura: 31 min

Seventy years of ideas turning into companies—and companies turning into infrastructure: why generative AI is not just a technology, but a stress test of governance, capital, and trust.

By Andrea Viliotti (GDE framework) — February 13, 2026

· GenAI makes the digital world’s “physical” constraints visible again: chips, energy, cloud, data, and rules.

· Re-reading the history of tech entrepreneurship helps separate innovation that scales from innovation that fizzles—or gets absorbed—when the context shifts.

· Three recurring destinies—success, failure, acquisition/absorption—are not “events.” They are outcomes of choices about organization, incentives, technology, capital, and habitat.

· In the GenAI era, the center of gravity shifts once more: from product to infrastructure, from talent to supply chain, from hype to auditability.

The history of digital entrepreneurship is, at its core, a story of time compression. Each technological generation—transistors, microprocessors, personal computers, the web, smartphones, cloud, deep learning—lowered the cost of doing something, and raised the cost of doing it well. “Well” now means reliable, governable, scalable, and defensible. Generative AI (GenAI) is the latest wave, but with a decisive difference: it lands directly in cognitive work and language production. That is why it matters for firms, geopolitics, geoeconomics, labor, philosophy and culture, generational turnover, and civil society.

Timeline: how digital becomes entrepreneurship (1955–January 2026)

The starting point is not an app, nor the romanticized garage. It is a lab—and an organizational decision: assemble scarce capabilities and take capital risk on a production chain that is still uncertain. What we now call Silicon Valley is born from that three-way handshake between research, industry, and financiers willing to underwrite rapid iteration.

In 1955, William Shockley and Arnold Beckman agreed to found the Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory; a generation of engineers passed through it and soon after created Fairchild Semiconductor, among the first companies to manufacture transistors and integrated circuits at commercial scale.12

From that lineage comes Intel (1968) and, with Intel, the idea that advantage is not merely “having a product” but being the curve: investing systematically in R&D, standardizing, building supply chains, and shaping a shared language—architectures, tools, compatibility.45

During those same years, European digital entrepreneurship follows a different path: less “betting on the chip,” more “betting on the process.” SAP is founded in 1972 by former IBM employees on a simple, radical idea: standard software to integrate enterprise processes in real time. It is entrepreneurship that grows inside the need for organization, not inside the myth of disruption.10

And there is an Italian chapter, too—often treated as a footnote but in fact essential: Olivetti’s Programma 101 (1965) is introduced as a “desktop computer” when computers are still machines for the few. It foreshadows a lesson that will return: digital value materializes when it becomes an object and a workflow—not when it remains a technical demo.4041

Timeline (quick read) 1955–1957 — Shockley Lab → Fairchild: the “research + capital + manufacturing” model that builds the chip stack. 1968–1972 — Intel and SAP: two complementary paths—scalable hardware and organizational software. 1975–1976 — Microsoft and Apple: the PC as a platform; software as the leverage of standards. 1989–1991 — The Web at CERN: open standards that slash the cost of distributing information. 1994–1999 — Amazon/Google and the web wave; Netscape enters AOL’s orbit: distribution becomes power. 2000–2014 — Platforms, advertising, and digital supply chains; China scales with Alibaba and Tencent. 2010–2022 — Deep learning, cloud, foundation models; the Transformer (2017) accelerates the paradigm shift. 2022–Jan 2026 — ChatGPT and GenAI: mass adoption, new governance, new asymmetries across compute/data/rules. Read: digital becomes entrepreneurship when it moves from “artifact” to “standard” and then to “infrastructure.” Each scale jump shifts the constraints: from technology to organization, from market to geopolitics. |

1955–1979: from the lab to the personal computer (and software as a standard)

The first “business model” of the digital era is not an app. It is manufacturing repeatable components. The transistor, and later the integrated circuit, do two things at once: they miniaturize and they standardize. Miniaturization enables diffusion; standardization enables an ecosystem—suppliers, compatibility, transferable skills.

When Bill Gates and Paul Allen found Microsoft in 1975, they are betting on a thesis: software is not hardware’s accessory—it is the interface that decides what hardware can do and who gets to do it. A year later, Jobs and Wozniak found Apple and bring a second insight: personal computing is a cultural object, so design and experience matter as much as the motherboard.86

This is where a pattern is born that will run all the way to GenAI: companies that endure do not separate “technology” from “organization.” They build a shared language—APIs, tools, documentation, partners—that reduces friction for everyone else. In practice: they make themselves easy to adopt and hard to replace.

1980–1999: the Web opens markets, but scale creates the first absorptions

The 1980s and 1990s are when digital leaves the back office and meets the network. In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee proposes at CERN a system to link documents across different computers: the World Wide Web is born. It is not just a technical invention; it is an implicit pact around open standards that dramatically lowers the cost of publishing and discovering information at global scale.11

The network creates entrepreneurship in two ways. First, it opens new markets—e-commerce, search, advertising. Second, it reshapes power: whoever controls access (browsers, portals, protocols) can redraw the value chain. Netscape sees it early: the browser becomes a control point. When AOL acquires Netscape in 1999, the episode is often remembered as dot-com bubble trivia; it is also a maturation signal: distribution is worth as much as technology.1213

Caption: a five-node chain (standards/protocols → browsers and operating systems → portals/search → advertising/monetization → data/feedback). Read: as the Web shifts from content to distribution to data, power tends to migrate toward whoever controls access and learning from behavior. |

In the same period, a second pattern consolidates: acquisition as an “industrial outcome.” It is not necessarily a failure; often it is what happens when a promising technology cannot sustain the cost of competing at global scale, or when operating inside an incumbent’s perimeter becomes the channel to reach billions of users. You can see it later with Skype, acquired by Microsoft in 2011: Internet communication turns into a platform asset.14

2000–2014: platforms, the dot-com selection, and China’s digital scale

The dot-com bust does not erase digital entrepreneurship—it selects it. Amazon (founded in 1994) survives the lean years by transforming from an online bookstore into logistics infrastructure and, later, cloud; Google (1998) turns search into a machine for advertising and data. In both cases, what matters is not only the product: it is a scale feedback loop—users → data → improvement → more users—that compounds into cumulative advantage.1517

But the same era also produces “textbook” failures: Webvan, the emblem of e-grocery, shuts down and files for Chapter 11 in 2001; Pets.com adopts a liquidation plan in 2000–2001. The lesson is not moralistic—it is structural. When fixed costs (warehouses, delivery, customer service) grow faster than demand, technology will not save the model. Logistics innovation is not enough if finance prices in a scale the operation cannot actually sustain.3739

Meanwhile, China builds its own ecosystem: Alibaba is founded in 1999 and becomes a marketplace-and-services platform; Tencent (1998) starts from messaging and expands into digital services. China’s story is often framed as “copying” U.S. models; it is more accurately an adaptation to a different habitat, where the relationship between state, platforms, and industry is tighter.1921

Timeline (1994–2014): few cases, many lessons Successes: Amazon (logistics → infrastructure), Google (search → data → advertising). Failures: Webvan and Pets.com (costly scale-up without sustainable unit economics). China: Alibaba and Tencent (platforms that integrate services, payments, distribution). Read: success becomes more likely when a platform controls at least one of (a) distribution, (b) infrastructure, (c) standards. Failure risk rises when fixed costs get too far ahead of real demand. |

2015–2022: deep learning, cloud, foundation models—toward GenAI

The wave that leads to GenAI comes from the intersection of three factors: (1) more capable statistical models, (2) more available data, (3) cloud infrastructures that make training scalable. A key theoretical inflection is the Transformer (2017), an architecture that makes sequence learning more efficient and enables a new generation of language models.30

In this context, OpenAI is founded (2015) and, over time, evolves its structure and partnerships to scale research and deployment. The most important transformation is not only technical—it is organizational. When the model is general-purpose (foundation), risk does not stay inside an IT department: it touches governance, policy, rights, and accountability. That is why, alongside innovation, attention grows around risk-management frameworks. Among the most widely used, the NIST AI RMF 1.0 (2023) structures work into four functions—Govern, Map, Measure, Manage—and emphasizes the role of “AI actors” across the lifecycle.2732

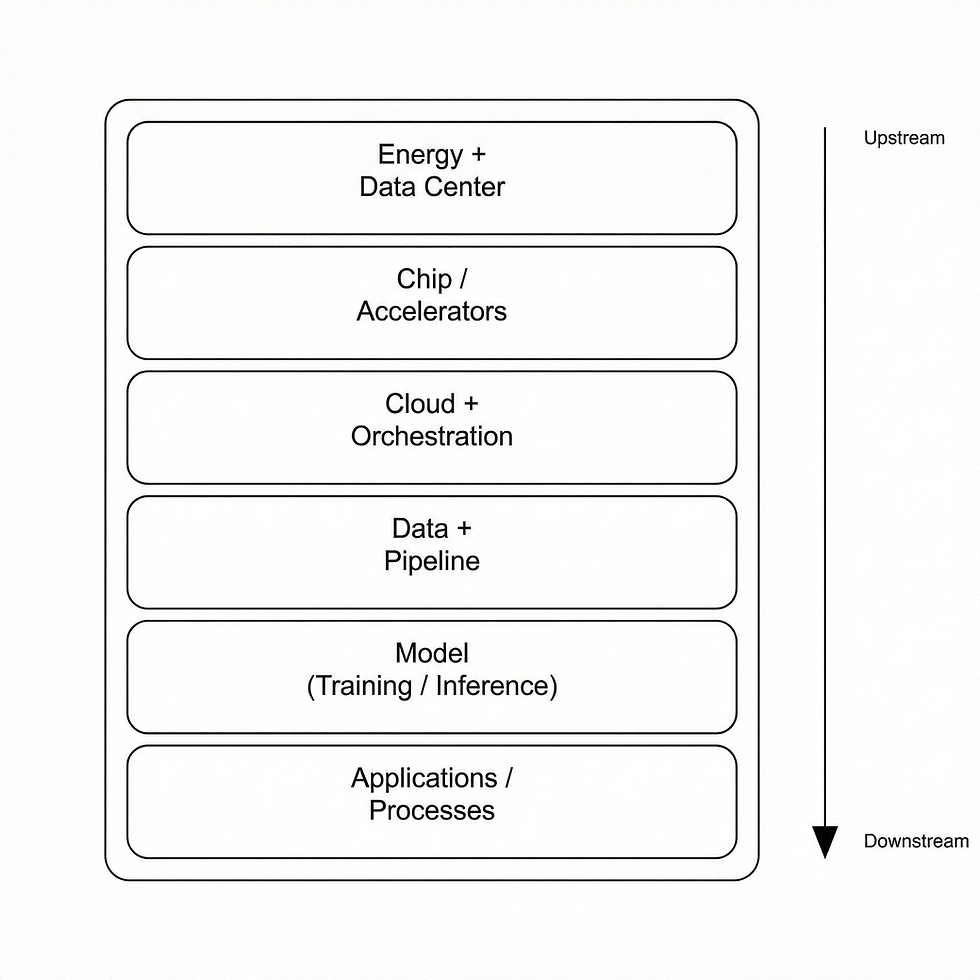

Caption: six layers (energy + data centers → chips/accelerators → cloud/orchestration → data/pipelines → model → applications/processes). Read: a GenAI-native company is dependent on external suppliers across multiple layers; upstream fragility (policy, prices, export controls, outages) can propagate downstream. |

2022–January 2026: ChatGPT, industrial divergence, and the return of constraints

On November 30, 2022, OpenAI releases ChatGPT as a “research release.” It is a cultural event before it is a technical one. For the first time, a language model—accessible to anyone—shows enough capability to enter writing, programming, and document production. From that moment, GenAI stops being a conference topic and becomes competitive pressure.2829

From there, two divergences open up. The first is industrial: GenAI-native companies emerge with distinct strategies (closed vs. open weights, vertical integration vs. platform). In Europe, for instance, Mistral AI is founded in 2023 with an explicit positioning around efficient models and partial openness. The second divergence is regulatory: the EU passes the AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689), bringing an operational vocabulary into the market—risk, transparency, obligations along the value chain.3433

But GenAI does not live in a vacuum. It brings back to the foreground the “physical constraint” of the digital economy: compute, chips, energy, data centers. If the web era could start with one server and a good idea, here infrastructure costs and lead times become part of strategy. That is one reason some analysts talk about a “multi-bubble”: not one price, but a chain of constraints—financial markets, capex, semiconductors, energy, geopolitics.46

Finally, there is a cultural layer. If the web transformed access to information, GenAI transforms the production of meaning. The encounter between “logos” and “dao”—to borrow a philosophical metaphor—is not a literary flourish. It is a question about what we consider true, fair, and delegable to automated systems—in markets as much as in states.45

Method note (no numbers): what changes with GenAI • From product to process — AI enters procedures (write, decide, control). • From feature to governance — competitive differentiation shifts toward auditability and risk management. • From “digital” scale to “physical” scale — compute, data, energy, and supply chain become advantages (or constraints). Read: GenAI accelerates time-to-market, but increases the cost of trust. |

Three destinies (GDE): success, failure, acquisition/absorption

To read seventy years of digital entrepreneurship without getting lost in folklore, you need a grid. Here I use an auditable GDE grid that looks at the transition idea → organization → scale and classifies outcomes into three operational destinies: success (sustainability + scale), failure (shutdown/insolvency), acquisition/absorption (integration into a larger perimeter).

Caption: a four-stage funnel with three recurring exits (advance, stop/failure, acquisition/absorption). Below: an observability bar—typical proxies by stage (documents; market signals; technical signals; organizational signals). |

Table 1 — Qualitative matrix: typical signals by destiny (excerpt).

Dimension | Success (sustainable + scalable) | Failure (shutdown/insolvency) | Acquisition/absorption (integration) |

Idea | Real problem + timing; clear wedge | Vague problem; forced timing | Valid wedge but too narrow to sustain global competition |

Founders | Complementary skills; fast learning | Ego/distorted incentives; leadership churn | Great team but incomplete (missing go-to-market or governance) |

Early backers | Patient capital + governance | Hype/term sheet that forces premature scale | Strategic/CVC oriented toward integration |

Habitat | Ecosystem of talent, pilots, partners | Hostile habitat (rules, supply, talent) | Habitat that rewards consolidation and concentration |

Tech model | Modularity, reliability, testing | Tech debt + fragile supply | “Plug-in” tech for incumbents; integration-ready |

Business model | Compounding distribution; retention | Unresolved unit economics; high fixed costs | Strong product, weak distribution; exit via channel owner |

Weak signals | Transparency, healthy metrics, incident culture | Orphan numbers; storytelling without audit | Roadmap optimized for partnerships; dependence on one gatekeeper |

Read: the matrix does not “predict” the future. It exists to make cases across time comparable and to translate weak signals into observable decisions (go/no-go, pace of scaling, partner choices).

Read: acquisition is often the outcome of a mismatch between technical value and distribution capability, or of a geopolitical/industrial choice to consolidate.

Profile type A — The “scaler” (likely success)

Idea: Framed as measurable friction reduction (time, cost, error) and stays legible even as the underlying technology shifts.

Founders: Complementary skills (product/technical/go-to-market) and the ability to change your mind without changing the mission.

Early backers: Capital and governance that reward learning (verifiable milestones) more than nominal growth.

Habitat: Access to talent, pilot customers, and partners that turn a prototype into a repeatable process.

Organizational model: Small teams with clear ownership; ability to “federalize” as complexity grows.

Management model: Decision rhythms and rituals that surface trade-offs and incidents; explicit accountability.

Tech model: Modularity, testing, observability; attention to supply chain and critical dependencies (cloud, data, chips).

Funding model: Aligned with real scale constraints (capex, working capital, compliance), not just the narrative.

Business model: Compounding distribution (network effects, lock‑in, switching costs) without destroying trust.

Determining weak signals: Solid documentation, metrics with owners, fast-correction culture, ability to say “no.”

Other factors: Ability to turn standards into advantage (APIs, compliance, certifications) and to negotiate with regulators.

Profile type B — The “over-scaler” (failure risk)

Idea: Vague pain point or “technology looking for a problem”; narrative outruns evidence.

Founders: Skill gaps (product or operations), or incentives optimized for fundraising/media rather than delivery.

Early backers: Terms that force speed; little patience for learning cycles; governance weak or absent.

Habitat: High dependence on external regimes (capital markets, regulation, supply chain) without contingency plans.

Organizational model: High fixed costs early; organizational complexity grows before product-market fit.

Management model: Metrics without owners; no incident culture; risk treated as PR.

Tech model: Technical debt; brittle data pipeline; dependence on a single vendor/partner.

Funding model: Burn-driven scale; cliff risk when capital conditions change.

Business model: Unit economics unresolved; distribution costs explode; churn hidden.

Determining weak signals: Aggressive expansion before evidence; internal dissent suppressed; “numbers orphaned.”

Other factors: Reputation crises or regulatory hits reveal weak governance; layoffs become the control mechanism.

Profile type C — The “component” (likely acquisition/absorption)

Idea: A strong piece of value (a component, model, or capability) but not a full stack.

Founders: High technical excellence; go-to-market and distribution weaker or intentionally de-prioritized.

Early backers: Strategic investors or a clear path to integration; acquisition is an explicit scenario.

Habitat: An industry where consolidation is rational (platforms, regulated markets, supply chains).

Organizational model: Built to be integrated: clean interfaces, documentation, compliance readiness.

Management model: Optimization for partnership milestones rather than standalone scale.

Tech model: “Plug-and-play” architecture; fits inside an incumbent’s platform or product line.

Funding model: Runway aligned with an exit window; dependence on one or two strategic gatekeepers.

Business model: Strong technology but fragile distribution; acquisition solves channel access.

Determining weak signals: Roadmap shaped by a partner’s needs; early commercial traction concentrated.

Other factors: Geopolitical and regulatory positioning can accelerate absorption (e.g., sovereignty, export controls).

Named CASEPACK (excerpt): emblematic cases by era and region

Case | Region | Period | Destiny | Why it’s in the dossier | Sources (notes) |

Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory | USA | 1955–1956 | Absorption (ecosystem) | Origin of the supply chain: talent “spreads” and founds new companies. | 1 |

Fairchild Semiconductor | USA | 1957– | Success → fragmentation | Archetype of spin-offs and chip standardization. | 2,3 |

Intel | USA | 1968– | Success | Hardware as industrial standard and supply chain. | 4,5 |

SAP | Europe (DE) | 1972– | Success | Process software (ERP) as enterprise infrastructure. | 10 |

Microsoft | USA | 1975– | Success | Software as the leverage of standards; platform logic. | 8,9 |

Apple | USA | 1976– | Success | Vertical integration and “experience” as a moat. | 6,7 |

The Web (CERN) | Europe (CH) | 1989–1991 | Success (standard) | Open standards that change distribution and publishing costs. | 11 |

Netscape → AOL | USA | 1998–1999 | Acquisition/absorption | Browser as control point; scale shifts from product to channel. | 12,13 |

Amazon | USA | 1994– | Success | Logistics + cloud: from retail to infrastructure. | 15 |

USA | 1998– | Success | Search → advertising/data flywheel. | 17 | |

Webvan | USA | 1996–2001 | Failure | Costs outrun demand; scale-up without sustainability. | 37,38 |

Pets.com / IPET | USA | 1998–2001 | Failure | E-commerce hype without unit economics. | 39 |

Alibaba | China | 1999– | Success | Platform + trust in transactions; ecosystem build-out. | 19,20 |

Tencent | China | 1998– | Success | Messaging → super-app; adjacent expansion. | 21,22 |

OpenAI | USA | 2015– | Scale in progress | Foundation-model stack + governance stress test. | 27,28,32 |

Mistral AI | Europe (FR) | 2023– | Scale in progress | European GenAI-native firm; openness vs sustainability trade-offs. | 34,59 |

Anthropic | USA | 2021– | Scale in progress | Safety-oriented positioning; competition on governance. | 33 |

Read: the CASEPACK is intentionally sparse—few cases per era, chosen for signal density. It is not an exhaustive history.

Read: the same company can move between destinies over time; here “destiny” is used as an operational classification for the period and the dominant outcome.

Geoeconomic lens: USA, Europe, China—and Italy as an application tail

United States: where entrepreneurship becomes infrastructure

The U.S. story is not only a story of startups; it is a story of platforms turning into infrastructure. From Intel to Microsoft to the web era, a recurring pattern is control over standards and interfaces. In the platform era, distribution and data become the key assets: search, mobile OS, cloud, ad networks.

In GenAI, the U.S. maintains an edge in research and capital, but faces a new constraint: infrastructure. Compute, chips, energy, and data-center build-outs turn into strategic variables; they also increase geopolitical exposure.

Europe: industrial depth, fragmented scale

In Europe, the trajectory is more fragmented and more “industrial.” Building processes (ERP, supply chain, machines, standards) is an advantage, but can become a brake when scale requires concentration. Arm (founded in 1990) shows how Europe can create deep technology standards; Spotify (founded in 2006) illustrates a different kind of success: a consumer platform that wins on user experience and supply-chain agreements.2325

In GenAI, Europe’s challenge is less about talent and more about creating durable routes to scale: capital markets, procurement, a unified market, and credible compliance capacity that does not suffocate experimentation.

China: scale as coordination

China shows that digital scale is not only about “innovation,” but also about institutional coordination. Alibaba and Tencent are two examples of ecosystems that integrate services, payments, and platforms. For Western observers, the lesson is not “imitate,” but recognize that habitat (rules, capital, state capacity, supply chains) determines which organizational models become sustainable.2022

Italy: the application tail (and the governance opportunity)

Italy often enters digital as a user, integrator, supplier of high-quality niches. Olivetti’s history reminds us that this is not destiny—it is a choice of habitat and capital. Today Italy’s lever is application: bringing technologies (cloud, AI, automation) into real processes (manufacturing, logistics, public administration). But that is precisely why GenAI is a hard test: when it enters processes, it demands measurement, accountability, and a method for deciding without illusions.4047

A useful industrial case—also symbolically—is STMicroelectronics: born in 1987 from the merger of two European entities, it shows that scale can be built even on a continent of compromises. On the other side, cases like Yoox Net‑A‑Porter show an e‑commerce “supply-chain” trajectory: fashion, logistics, and digital capabilities that become an acquirable asset.4244

Read: there are no universal recipes. The same technology produces different companies depending on capital, rules, managerial culture, and supply chains.

Observers and weak signals: who can see what, and when

The operational question is not “what will AI do?” but “who can see the signals before they become crises?” GenAI amplifies a long-standing problem of digital systems: many critical decisions happen far from the observation of those who bear the impacts. The NIST AI RMF stresses that lifecycle actors are different and have partial visibility; that is why we need an observer map.31

Table 2 — Observer map: visibility, weak signals, proxies, biases, levers.

Observer | What they can actually see | Weak signals | Observable proxies | Typical biases | Levers & timing |

Research / universities | Technical quality, publications, tools | Drift between benchmarks and real-world use | Papers, repos, public evals | Underestimate product costs | Idea → startup: validate limits |

Founder team | Vision, execution, culture | Metrics without an owner; opaque dependencies | Roadmap, incident log, churn | Overconfidence, survivorship bias | All stages: governance |

Early employees | Real culture, friction, security | Burnout, turnover, “hero culture” | Exit rate, ticket backlog | Fear of speaking up | Startup → scale-up: raise alerts |

Incubators / accelerators | Team, market, network | Pitch too “market,” not enough “operations” | Demo vs. pilot | Selection for storytelling | Idea stage: filter the wedge |

Angels / VC / CVC | Cap table, milestones, burn | Forced growth, safety debt | Term sheet, covenants, hiring plan | Hype, FOMO | Startup → scale-up: stop/go gates |

Pilot customers / procurement | Value in process, operational risk | Unverifiable output; exception escalations | SLA, audit trail, incidents | Vendor lock‑in | Pilot → rollout: exit criteria |

Integrators / supply-chain partners | Compatibility, integration costs | Critical dependencies, API fragility | Cost-to-integrate, change logs | Commercial optimism | Scale-up: standardize |

Board / legal / compliance | Risk, liability, policies | Gray zones on data/IP | Policies, DPIA, contracts | Excessive conservatism | Pre-deploy: govern go/no-go |

Risk managers / auditors | Controls, incident response | Missing logging; impossible overrides | Audit reports, TEVV tests | Checklists without context | Operate: monitor and correct |

HR / unions | Role impact, skills, turnover | Junior bottlenecks | Hiring pipeline, training | Defend the status quo | Adoption: redesign roles |

Regulators / standard bodies | Systemic risks, compliance | Asymmetries in transparency | Reports, compliance evidence | Slow cadence | Market: set baselines |

Civil society / communities | Impact, trust, harm | Rage bait, misinformation, bias | Reports, civic audits | Polarization | Post-deploy: feedback and pressure |

Read: every observer sees only a slice. The practical goal is to connect slices with artifacts: documents, logs, contracts, audits, and feedback loops.

Read: weak signals are most valuable when they are tied to a lever: stop, slow down, pivot, renegotiate, or redesign governance.

In the attention economy, a distinctive risk is that recommendation algorithms optimize for outrage (“rage bait”), with spillovers into reputation, polarization, and trust. For companies, this is operational risk: brand safety, internal communication, and relationships with impacted communities.49

Forecast GDE (GenAI-native): a qualitative playbook for observers

Here “forecast” does not mean predicting numbers or valuations. It means increasing our ability to recognize early patterns that historically lead to one of the three destinies. For GenAI-native firms, risk is twofold: (a) infrastructure constraints (compute/data/energy), (b) trust constraints (security, bias, IP, compliance). The playbook below uses observable weak signals and ties them to practical decisions across the lifecycle.

Golden rule (anti-illusion) If you can’t explain who owns a metric, how it’s measured, and what happens when it gets worse, that metric is noise (even if it’s a number). Read: GenAI increases speed; governance exists to prevent “cognitive surrender”—delegating the criterion to the model. |

In cognitive work, surrender can be silent: outputs accepted without verification, decisions that look rational because they are well-written. To counter it you need organizational friction: review, reading groups, audit trails, and TEVV (test, evaluation, verification, validation).5031

Table 3 — Checklist (weak-signal playbook) for GenAI-native firms, by lifecycle stage.

Stage | What must be true | Positive weak signals | Red flags (hazard) | Most likely destiny if not corrected |

Idea | Defined problem + use context; hypotheses on data/compute; boundaries of responsibility. | Clear wedge (one process); metrics with an owner; data/IP policies explicit early. | Pitch centered on “model magic”; cloud dependencies not disclosed; no evaluation plan. | Failure or early acquisition |

Startup | MVP that reduces risk; data pipeline; minimal security and logging; clear contracts. | Pilot with real users; incident log; repeatable evals; kill switch and overrides. | Demo-only; inference costs out of control; IP conflicts; no TEVV. | Acquisition (talent/IP) or stop |

Scale-up | Distribution and compliance; supply resilience; cross-functional governance. | SLA, audit trail, red-teaming; supplier diversification; learning loop. | Vendor lock‑in; security failures; quality drift; regulatory pressure. | Acquisition/absorption or reputational crisis |

Company | Industrialization; continuous risk management; responsibility toward impacted communities. | Post-deploy monitoring processes; transparency; resources for response and recovery. | Rage bait/abuse; repeated incidents; opacity on data; talent flight. | Decline or punitive regulation |

Read: the checklist is not a compliance exercise. It is a decision aid: when a red flag appears, you either add governance capacity or you change the scaling path.

Read: for GenAI-native firms, a recurring failure mode is “infrastructure blindness”: assuming compute and data are commodities until they become constraints.

NIST AI RMF as an “actor map” (adapted to the playbook) GOVERN: policies, roles, accountability, system inventory. MAP: use context, impacts, actors involved, initial go/no-go. MEASURE: evaluations, tests, metrics for reliability and risk. MANAGE: risk treatments, post-deploy monitoring, incident response, decommissioning. Read: the framework is useful because it makes explicit the separation between who builds and who verifies. Reference: NIST AI RMF 1.0. |

This scheme comes from the NIST AI RMF and is used here as a bridge between governance and observability: for each function, ask which artifacts exist and who can actually control them.31

A dialogue with management literature (without overclaim)

Many ideas here are not new. Christensen showed how large companies can fail not because they don’t innovate, but because they optimize for existing customers and margins (“the innovator’s dilemma”). Steve Blank, and later Eric Ries, popularized another insight: a startup is not a “small company”—it is a learning machine under uncertainty (customer development, MVP, validated learning). Thiel insisted on differentiation and “zero to one.”54555657

The GDE grid used in this dossier does not claim to replace these approaches. It binds them to an operational question: how do we move from useful concepts (disruption, MVP, zero-to-one) to observable signals—with owners, metrics, and decision gates? And how does the answer change when the technology is GenAI and it involves language, trust, and regulation?

Read: GenAI makes the least celebrated part of the management literature more urgent—governance, incentives, and decision quality.

Executive summary

· Digital entrepreneurship is a history of compounding: standards → ecosystems → platforms → infrastructure.

· GenAI is not only an innovation wave; it is a stress test of the supply chain (compute/chips/energy) and of trust (governance/auditability).

· Three destinies—success, failure, acquisition/absorption—can be analyzed with an auditable grid across idea, founders, capital, habitat, organization, management, technology, funding, and business model.

· Observers matter: weak signals are visible in different places (research, founders, employees, investors, customers, regulators, civil society) and at different times.

· For GenAI-native firms, early governance capacity (inventory, evaluation, logging, contracts, incident response) is a leading indicator of sustainability.

Risk radar (2026)

· Supply‑chain risk (compute/chips/energy): critical dependencies and costs can shift fast; diversification and contracts matter.46

· Regulatory and compliance risk: risk-based obligations along the value chain (transparency, risk management) become part of go‑to‑market.3331

· Reputational and trust risk: the attention economy and rage bait can turn a fragment into a crisis; you need friction and governance.49

· Organizational risk (turnover and skills): automating junior work can create generational bottlenecks; rethink entry-level roles and training.52

· Cognitive‑surrender risk: delegating the criterion to the model reduces control capacity; introduce reviews, audit trails, and TEVV.5031

State of facts (January 2026): what we can say without overclaim

Table 4 — Claim-status block (PUBLIC-ONLY).

Claim | Status | Notes | Why it matters |

Shockley Lab (1955) and Fairchild (1957) are foundational nodes of Silicon Valley | VERIFIED | 1,2 | Origin of the research + capital + manufacturing model |

Intel is founded in 1968 | VERIFIED | 4 | Chip standards and supply chain |

Microsoft (1975) and Apple (1976) emerge as PC/software companies where software becomes a standard | VERIFIED | 8,6 | Software becomes platform |

The Web is invented by Tim Berners‑Lee at CERN in 1989 | VERIFIED | 11 | Open standards and lower distribution costs |

AOL completes the acquisition of Netscape in 1999 | VERIFIED | 12,13 | Distribution as power |

Webvan enters Chapter 11 in 2001; Pets.com adopts a liquidation plan in 2000–2001 | VERIFIED | 37,39 | Failures driven by fixed costs and premature scale |

Transformer (2017) is an architectural inflection for language models | VERIFIED | 30 | Technical base of foundation models |

ChatGPT is released on November 30, 2022 | VERIFIED | 28,29 | Cultural event of mass adoption |

EU AI Act (Reg. 2024/1689) introduces risk‑based obligations | VERIFIED | 33 | Governance becomes a competitive variable |

The “multi‑bubble AI” as a chain of constraints is an interpretive frame (not a fact) | HYPOTHESIS / FRAME | 46 | Useful for qualitative stress‑testing, not for pricing |

Read: where a claim is not supported by primary sources, it is explicitly downgraded to hypothesis/frame in the audit appendix.

What to do: six operational moves (GenAI in firms, without illusions)

1. Treat GenAI as a system, not a tool — define roles (process owner, model owner, compliance, security) and introduce review rituals and incident reviews.5131

2. Inventory and classification (before you scale) — build an inventory of use cases and models; for each, define context, data, risk, and metrics.31

3. Use-case selection: start from the constraint, not the demo — choose where to reduce measurable friction; avoid “orphan numbers” and set stop/exit criteria.47

4. Procurement and contracts: make data, IP, logging, and audit explicit — governance is also purchased: clauses on incident reporting, change management, overrides, and decommissioning.3133

5. Redesign work (especially entry-level) — if GenAI automates junior tasks, build a plan: new roles, mentoring, training, rotations.52

6. Well-being and productivity: avoid the paradox of innovation that burns the team — ROI depends on organizational conditions (load, trust, transparency).53

What to monitor in 2026: observable signals (no oracles)

· Supply chain & compute: cloud contracts, single‑vendor dependencies, provisioning lead times, inference cost/latency by use case.

· Governance & compliance: existence of policies, audit trail, evidence pack for the AI Act; incident‑response capacity.

· Quality of cognitive work: overreliance on outputs, reduced verification, repeated‑error escalations.

· Distribution & trust: rage‑bait signals, reputation crises, community polarization, transparency on model changes.

· Capital & scaling pace: pressure to scale before sustainability; mismatch between capex and real demand.

· Method references: NIST AI RMF and qualitative stress‑testing along the constraint chain.314633

Red thread

The red thread in this story is that digital entrepreneurship does not grow “against” institutions; it grows inside an equilibrium among ideas, capital, and rules. Every time a technology lowers a cost, someone shifts power by defining the standard: today that means APIs, cloud policies, models, and datasets; yesterday it was chips, operating systems, and browsers. Digital’s promise is speed; its price is dependency. And when dependency becomes systemic, geopolitics enters the cost function: semiconductor supply chains, export controls, energy, data centers, regulation. That is the “concert of power”: a continuous triangulation among platforms, the state, and companies that need to stay operational.48

In that equilibrium, GenAI is a harder test because it touches language, and therefore trust: decisions, documents, training, reputation. It is not enough to ask which model to adopt; you need to ask what kind of organization you become when a system proposes “well-written” answers—and when incentives reward the content that divides. For Italy, which often plays the game as an integrator and manufacturing base, the challenge is to turn constraint into advantage: make governance (auditability, security, process) into a product rather than a cost. In other words: make innovation not a technical bet, but a resilience choice.4749

Essential bibliography (selection)

· NIST — Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0), 2023 (note 31).

· European Union — Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (AI Act), Official Journal (note 33).

· Vaswani et al. — “Attention Is All You Need”, 2017 (note 30).

· OpenAI — “Introducing ChatGPT”, 2022 (note 28).

· Christensen — The Innovator’s Dilemma, 1997 (note 54).

· Blank — The Four Steps to the Epiphany (Customer Development), 2005 (note 55).

· Viliotti — selection of GDE analyses on governance, multi-bubble, labor, and trust (notes 48, 46, 47, 49).

APPENDIX — GDE Audit (PUBLIC‑ONLY)

This appendix documents sources, assumptions, alternative interpretations, and quality gates. It is designed to make the dossier auditable. The “Forecast GDE” section in the MAIN is a qualitative playbook (checklists and weak signals), not a numerical forecast.

A1 — Data block freeze (sources used in the MAIN)

Table A1 lists the public sources used for the MAIN (selection).

Note ID | Institution / publisher | Short title | Source type | URL |

1 | Computer History Museum | 1956: Silicon Comes to Silicon Valley | Institutional | |

2 | Encyclopaedia Britannica | Fairchild Semiconductor | Reference / institutional | |

4 | Intel (corporate history) | Intel founding (1968) | Primary source (corporate history) | |

8 | Microsoft founded (1975) | Reference / business press | ||

6 | Library of Congress | Apple Computer founded (1976) | Institutional archive | |

11 | CERN | The Birth of the Web | Institutional | |

12 | The Washington Post | AOL and Netscape merger (1999) | Business press / primary report | |

33 | European Union (Official Journal) | Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (AI Act) | Institutional (law) | |

30 | arXiv | Attention Is All You Need (Transformer) | Research (paper) | |

31 | NIST | AI RMF 1.0 | Institutional / standards | |

46 | The “multi-bubble AI” frame | Analysis / method (author) |

Read: source selection is intentionally conservative (institutional, research, business press). Where a claim is load‑bearing, the KZ‑2L12 gate requires multiple independent sources.

A2 — KZ‑2L12 gate: load‑bearing claims must be supported

This section documents which claims are considered “load‑bearing” and how they are supported (or downgraded).

Load‑bearing claim | Source #1 | Source #2 | Outcome | Notes |

1955 Shockley Lab + 1957 Fairchild as origin nodes of Silicon Valley | 1 | 2 | OK | Used as historical anchor; no numeric inference. |

Intel (1968) as standard hardware company; supply‑chain role | 4 | 5 | OK | Two sources incl. corporate history + Wikipedia quick reference. |

Web (1989) at CERN; open standard | 11 | — | OK | Institutional source. |

Transformer (2017) as inflection point for LLMs | 30 | — | OK | Primary paper. |

ChatGPT released 30 Nov 2022 | 28 | 29 | OK | Primary announcement + press coverage. |

EU AI Act (Reg. 2024/1689) sets risk obligations | 33 | — | OK | Official journal. |

“Multi‑bubble AI” as chain of constraints | 46 | — | DOWNGRADE | Author frame; not treated as fact. |

Rage bait as an attention‑economy risk dynamic | 49 | — | OK | Used as risk frame; not a fact about any one platform. |

GenAI affects labor and junior roles (deskilling / bottleneck) | 52 | — | OK | Single source; treated as scenario. |

Productivity vs well‑being paradox | 53 | — | OK | Single source; used as caution. |

Management literature references: Christensen, Blank, Ries, Thiel | 54 | 55 | OK | Canonical texts; no claim of completeness. |

NIST actor map as governance anchor | 31 | — | OK | Primary standard. |

Read: a DOWNGRADE is not “wrong.” It means the statement is treated as interpretation, not evidence.

A3 — Casepack profile blocks (audit summaries)

Note: these profile blocks are simplified on purpose. Tags indicate evidence level: [DATI(E)] verified, [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE] working hypothesis, [NON STIMABILE_GDE] not estimable from public sources in this dossier.

Case: Apple (1976–)

Main sources: Library of Congress, Apple founding (note 6); Wikipedia quick reference (note 7).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Personal computing as an accessible, usable product [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | Jobs + Wozniak (tech + product) [DATI(E)]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | Emerging California PC ecosystem [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Integrated product company; HW/SW integration [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Experience and platform control focus [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Integrated architectures [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Business model: | Hardware + ecosystem [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Design as advantage; control of the interface [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Brand and retail distribution [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Microsoft (1975–)

Main sources: HISTORY.com (note 8); Wikipedia quick reference (note 9).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Software for the PC; standardization [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | Gates + Allen [DATI(E)]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | Emerging PC ecosystem, demand for developer tools [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Software company scaling on standards [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Partner and platform dynamics [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Operating systems and developer tools [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Business model: | Licensing and ecosystem [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Control of APIs and compatibility [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Network effects among developers [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Webvan (1996–2001)

Main sources: Wikipedia quick reference (note 37); The New York Times coverage (note 38).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Online grocery delivery at scale [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Early backers: | VC funding (details not here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | Dot‑com boom; high expectations [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Capex‑heavy logistics [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Aggressive expansion [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | E‑commerce + warehouses [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | High burn [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Business model: | Low margin, high fixed cost [DATI(E)]. |

Determining weak signals: | Unit economics not proven; warehouses ahead of demand [DATI(E)]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Bankruptcy (Chapter 11) in 2001 [DATI(E)]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Pets.com / IPET (1998–2001)

Main sources: Wikipedia quick reference (note 39).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Online pet products; brand marketing [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Early backers: | VC and IPO wave (details not here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | Dot‑com hype [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Marketing-heavy organization [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Spend-driven growth [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Simple e-commerce stack [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | Short runway [DATI(E)]. |

Business model: | Margins insufficient; shipping costs [DATI(E)]. |

Determining weak signals: | High CAC; low retention [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Liquidation plan 2000–2001 [DATI(E)]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Alibaba (1999–)

Main sources: Alibaba corporate history (note 19); Wikipedia quick reference (note 20).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | B2B/B2C marketplace + trust mechanisms [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | Jack Ma + team (details not here) [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | China: SME digitization + payments need [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Platform/ecosystem builder [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Expansion into adjacent services [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Marketplace + payments (Alipay) [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | Large rounds/IPO path (details not here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Business model: | Marketplace fees, services [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Network effects and trust in transactions [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Institutional/regulatory context [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Tencent (1998–)

Main sources: Wikipedia quick reference (note 21); Encyclopedia Britannica (note 22).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Messaging → platform services [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | Ma Huateng + team (details not here) [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | China: mobile, payments, content [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Ecosystem / super-app strategy [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Adjacent expansion and acquisitions [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Platforms, games, payments [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Business model: | Games, services, fintech [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | User lock‑in; super‑app dynamics [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Regulatory environment [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: SAP (1972–)

Main sources: SAP company history (note 10).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | ERP software to integrate processes in real time [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | Former IBM employees [DATI(E)]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | Europe: industrial firms need process integration [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Enterprise software company [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Long cycles, customer lock‑in [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | Standard software + customization [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Funding model: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Business model: | Licensing + services [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Standard adoption in enterprise [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | Global scale over time [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: OpenAI (2015–)

Main sources: OpenAI company page (note 27); ChatGPT release (note 28); NIST AI RMF (note 31); The Verge coverage (note 32).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Foundation models and GenAI applications [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | AI researchers + entrepreneurs (details not here) [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Early backers: | Partnerships/capital (details not here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | USA: capital, compute access [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | Hybrid structure; partnership with platforms [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Balance research and deployment under governance pressure [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | LLM stack; RLHF; tooling (not detailed here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Funding model: | Capex‑heavy; partnerships [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Business model: | APIs + products [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Governance events; safety posture; supply-chain dependence [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | NIST/RMF and regulatory pressure [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

Case: Mistral AI (2023–)

Main sources: Company page (note 59); EU AI Act (note 33).

Field | Summary (audit) |

Idea: | Efficient LLMs and European alternatives [DATI(E)]. |

Founders: | AI researchers (details not here) [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Early backers: | N/A [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Habitat: | EU: digital sovereignty and AI Act [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Organizational model: | AI startup with infrastructure ambitions [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Management model: | Balance openness and sustainability [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Technology model: | LLMs and toolchain (not detailed here) [NON STIMABILE_GDE]. |

Funding model: | Depends on rounds and partnerships [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Business model: | Models/services for enterprises [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Determining weak signals: | Cloud dependencies and compliance evidence [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Other factors surfaced: | European demand for alternatives [IPOTESI_LAVORO_GDE]. |

Read: “weak signals” and “management model” fields are often more predictive than the technical idea itself, because they expose governance capacity.

A4 — EQUATION_MAP — conceptual formula (GDE)

Goal: relate (a) technological power, (b) governance capacity, (c) physical constraints, (d) destiny.

Qualitative equation: DESTINY ≈ f(idea, founders, capital, habitat, org model, governance, supply chain, distribution, trust).

Note: this is not a numerical formula. It is an audit guide. If you can’t name the variables and their owners, you can’t govern the system.

A5 — Python binding (optional): how to use the CASEPACK as data

The CASEPACK and the qualitative matrices can be exported to a structured format (CSV/JSON) and used to build internal checklists, dashboards, and “evidence packs.” The key is to keep an explicit separation between facts, hypotheses, and interpretive frames.

Minimal schema: case_id, era, region, destiny, signals (docs/market/tech/org), governance_artifacts, supply_chain_dependencies, decision_gates, sources.

A6 — Data requirements for Forecast GDE (observer signals)

Table A6 lists suggested observable features (no personal data required) to operationalize the weak-signal playbook.

Feature | Description | Source | Frequency | Notes |

Supply dependency index | Number of critical suppliers (cloud, model API, chips) | Contracts / architecture | Quarterly | Higher concentration = higher fragility |

Inference unit cost | Cost per task / per token / per request | FinOps / logs | Weekly | Track drift after model changes |

Eval coverage | Share of use cases with documented evaluations | QA / model governance | Monthly | TEVV evidence pack |

Incident rate | Number and severity of incidents | Security / ops | Weekly | Look for repeated classes of failure |

Override usage | How often humans override model output | Workflow tools | Weekly | Can indicate poor quality or healthy governance |

Churn / retention | User or customer retention for AI features | Product analytics | Monthly | Separate novelty from value |

Compliance evidence readiness | Existence of documentation for obligations | Legal / compliance | Quarterly | AI Act mapping |

Training & skill hours | Hours spent on training and review rituals | HR / L&D | Monthly | Counteract deskilling |

Turnover heat | Attrition by role (esp. early-career) | HR | Monthly | Look for junior bottlenecks |

Public trust signals | Complaints, press, civic audits | External monitoring | Weekly | Rage bait and reputational risk |

Read: these features are proxies. They become useful only if they have owners and decision gates.

A7 — Quality gates log (internal)

This table logs which internal quality gates were applied to the dossier.

Gate | Test | Outcome |

DATA_BLOCK_FREEZE_v1 | Sources frozen on 2026‑02‑13 | OK |

KZ‑2L12_loadbearing | Load‑bearing claims cross‑checked | OK / DOWNGRADE where framed |

NO_NUM_FORECAST | No numeric forecasts in MAIN | OK |

OBSERVABILITY_PROXY | Observable proxies provided in MAIN | OK |

NIST_ANCHOR | RMF referenced as governance anchor | OK |

ITALIA_CODA_APPLICATIVA | Italy focus includes “application tail” lens | OK |

Read: quality gates reduce hallucination risk and make the framework reusable.

A8 — Assumptions and downgrades log (v1)

· [ASSUMPTION_GDE] The “Forecast GDE” playbook is qualitative: no numerical probability or valuation estimates.

· [ASSUMPTION_GDE] Where a second independent source is missing (KZ‑2L12), claims are phrased conservatively and marked as DOWNGRADE in Table A2.

· [NON_ESTIMABLE_GDE] No macro quantitative datasets (e.g., IMF WEO) were used: primary datasets were not frozen in this session.

· [WORKING_HYPOTHESIS_GDE] Some patterns (e.g., “feedback loop” and “standard as power”) are inferences: useful as a lens, not a universal law.

· [DATA(E)] NIST AI RMF is used as an institutional reference to map actors and lifecycle.

A9 — Next data actions (to increase robustness)

· [WORKING_HYPOTHESIS_GDE] Freeze PDFs/extracts of cited articles (andreaviliotti.it, HuffPost) to stabilize citations.

· [WORKING_HYPOTHESIS_GDE] Add second institutional sources for some claims (e.g., Web, AI Act, Transformer) to close KZ‑2L12 without downgrades.

· [WORKING_HYPOTHESIS_GDE] If you want macro boxes with numbers: include primary datasets (e.g., IMF WEO) and freeze a DATA_BLOCK_FREEZE with values and methodological notes.

· [WORKING_HYPOTHESIS_GDE] Extend the CASEPACK with additional European/Italian cases (acquisitions, failures) to balance outcomes.

Notes

[1] Computer History Museum; “1956: Silicon Comes to Silicon Valley”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.computerhistory.org/siliconengine/silicon-comes-to-silicon-valley/

[2] Encyclopaedia Britannica; “Fairchild Semiconductor | Definition, History, & Facts”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.britannica.com/money/Fairchild-Semiconductor

[3] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Fairchild Semiconductor”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fairchild_Semiconductor

[4] Intel; “Intel's Founding”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/history/virtual-vault/articles/intels-founding.html

[5] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Intel”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intel

[6] Library of Congress; “The Founding of Apple Computer, Inc.”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://guides.loc.gov/this-month-in-business-history/april/apple-computer-founded

[7] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Apple Inc.”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apple_Inc.

[8] History.com; “Microsoft founded | April 4, 1975”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/april-4/microsoft-founded

[9] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Microsoft”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microsoft

[10] SAP; “SAP History | About SAP”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.sap.com/about/company/history.html

[11] CERN; “The birth of the Web”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web

[12] The Washington Post; “AOL-Netscape Merger Official”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/business/1999/03/18/aol-netscape-merger-official/1443fa83-6b64-43d9-9c6a-d88e5961e6b9/

[13] Los Angeles Times; “With Netscape Stockholders’ OK, AOL Completes $9.6-Billion Buy”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-mar-19-fi-18746-story.html

[14] Microsoft News Center; “Microsoft to Acquire Skype”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://news.microsoft.com/source/2011/05/10/microsoft-to-acquire-skype-3/

[15] History.com; “Amazon is founded by Jeff Bezos | July 5, 1994”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/july-5/amazon-is-founded-by-jeff-bezos

[16] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Amazon (company)”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_(company)

[17] Google; “From the garage to the Googleplex (Our story)”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://about.google/company-info/our-story/

[18] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Google”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google

[19] Alibaba Group; “Introduction to Alibaba Group”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.alibabagroup.com/about-alibaba

[20] Encyclopaedia Britannica; “Alibaba | History, IPOs, Acquisitions, & Controversies”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.britannica.com/money/Alibaba

[21] Tencent; “About Us”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.tencent.com/en-us/about.html

[22] EBSCO Research Starters; “Tencent Holdings Ltd | History”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/tencent-holdings-ltd

[23] Arm Newsroom; “The Official History of Arm”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://newsroom.arm.com/blog/arm-official-history

[24] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Arm Holdings”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arm_Holdings

[25] Spotify Newsroom; “About Spotify”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://newsroom.spotify.com/company-info/

[26] EBSCO Research Starters; “Spotify (company) | Business and Management”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/business-and-management/spotify-company

[27] OpenAI; “Our structure”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://openai.com/our-structure/

[28] OpenAI; “Introducing ChatGPT”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://openai.com/index/chatgpt/

[29] History.com; “ChatGPT, the generative AI chatbot, is released”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/november-30/chatgpt-released-openai

[30] arXiv; “Attention Is All You Need”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

[31] NIST; “Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0)”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/nist.ai.100-1.pdf

[32] NIST; “AI Risk Management Framework | NIST”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework

[33] EUR-Lex (Unione europea); “Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 (AI Act) — Official Journal”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1689/oj/eng

[34] Mistral AI; “About us”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://mistral.ai/about

[35] Associated Press; “Anthropic hits a $380B valuation as it heightens competition with OpenAI”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://apnews.com/article/65c08aa4fab90cde952f37d32625394a

[36] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Anthropic”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthropic

[37] SFGATE / San Francisco Chronicle; “Webvan files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy with $106 million in debts”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Webvan-files-for-Chapter-11-bankruptcy-with-106-2899800.php

[38] Los Angeles Times; “Webvan Files for Chapter 11 Protection”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-jul-14-fi-22194-story.html

[39] U.S. SEC (EDGAR); “IPET Holdings Form 10-K (Pets.com) — Plan of Complete Liquidation and Dissolution”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1100683/000089161802001559/f80264e10-k.htm

[40] Fondazione Adriano Olivetti; “P101, when Olivetti invented the first personal computer”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.fondazioneadrianolivetti.it/en/p101-cecam/

[41] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Programma 101”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programma_101

[42] Wikipedia (quick reference); “STMicroelectronics”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STMicroelectronics

[43] strategy+business; “STMicroelectronics: The Metaphysics of a Metanational”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.strategy-business.com/article/20602

[44] MAM-e (fashion digital); “YOOX NET-A-PORTER”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://fashion.mam-e.it/yoox-net-a-porter/

[45] AndreaViliotti.it; “Quando il Logos incontra il Dao: una storia incrociata delle idee che oggi chiamiamo IA”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/quando-il-logos-incontra-il-dao-una-storia-incrociata-delle-idee-che-oggi-chiamiamo-ia

[46] AndreaViliotti.it; “La «multi-bolla IA» tra speculazione e strategia di potere”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/la-multi-bolla-ia-tra-speculazione-e-strategia-di-potere

[47] AndreaViliotti.it; “L’AI in azienda, senza illusioni: un metodo per decidere nel rumore geopolitico”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/l-ai-in-azienda-senza-illusioni-un-metodo-per-decidere-nel-rumore-geopolitico

[48] AndreaViliotti.it; “Il concerto del potere nell’economia digitale (2000–2026)”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/il-concerto-del-potere-nell-economia-digitale-dalla-piattaforma-alla-fabbrica-intelligente-2000-20

[49] AndreaViliotti.it; “Rage bait: l’economia dell’indignazione tra piattaforme, politica e fiducia”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/rage-bait-l-economia-dell-indignazione-tra-piattaforme-politica-e-fiducia

[50] AndreaViliotti.it; “Distant writing, social reading e governance dell’AI: come evitare la resa cognitiva”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/distant-writing-social-reading-e-governance-dell-ai-come-evitare-la-resa-cognitiva

[51] AndreaViliotti.it; “Dall’immunità adattiva ai LLM: perché l’IA in azienda funziona solo se la tratti come un sistema che impara”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.andreaviliotti.it/post/dall-immunit%C3%A0-adattiva-ai-llm-perch%C3%A9-l-ia-in-azienda-funziona-solo-se-la-tratti-come-un-sistema-che

[52] HuffPost Italia; “L'intelligenza artificiale rischia di rallentare il turn over”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.huffingtonpost.it/blog/2025/10/08/news/lintelligenza_artificiale_rischia_di_rallentare_il_turn_over-20222354/

[53] HuffPost Italia; “IA e produttività: perché il benessere è la leva che manca...”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.huffingtonpost.it/blog/2025/12/16/news/ia_e_produttivita_perche_il_benessere_e_la_leva_che_manca_alla_pubblica_amministrazione_e_alle_imprese_italiane-20752643/

[54] Harvard Business School; “The Innovator's Dilemma (1997) – bibliographic record”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=46

[55] Stanford University (hosting); “The Four Steps to the Epiphany (Customer Development Model) – Stanford handout (PDF)”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://web.stanford.edu/group/e145/cgi-bin/winter/drupal/upload/handouts/Four_Steps.pdf

[56] Wikipedia (quick reference); “The Lean Startup”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lean_Startup

[57] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Zero to One”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero_to_One

[58] Wikipedia (quick reference); “SAP”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SAP

[59] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Mistral AI”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mistral_AI

[60] Wikipedia (quick reference); “Spotify”; accessed February 13, 2026; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spotify

congratulations on this important analytical work